1. Overview: A Preventable Domestic Hazard with Life-Risk Consequences - September 2025

September 2025, a critical failure occurred within a private rented dwelling involving the heating and electrical systems.

A radiator bleed/isolation valve corroded and inadequately maintained failed catastrophically during a routine safety procedure, releasing large volumes of water into a workspace containing live electrical sockets, legal documentation, and computer equipment.

This incident did not arise in isolation. It occurred within a property already exhibiting serious electrical non-compliance, including a single-circuit socket configuration serving the entire premises, and followed repeated notifications to the landlord and local authority regarding unsafe conditions. Evidence of these hazards had also been submitted to the court in live proceedings but was not logged or addressed, mould near ceiling light, fire exit route blocked and live wire (wired and live wall lights with no switch.)

The incident represents a convergence of landlord neglect, local-authority non-action, and judicial suppression of safety evidence. All identifiers remain withheld pursuant to the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

2. Systemic Causation Statement

The heating failure was the foreseeable outcome of three concurrent institutional failures:

Landlord failure to maintain plumbing and electrical installations in lawful repair, despite visible corrosion and long-term degradation.

Local-authority failure to inspect or enforce under statutory housing-safety duties after notification of risk.

Judicial failure to register and consider safety evidence submitted within N244 applications in ongoing civil and possession proceedings.

Had any one of these actors fulfilled its statutory safeguarding duty, the radiator valve would not have reached the point of catastrophic failure. The hazard was preventable, foreseeable, and produced through cumulative neglect rather than accident.

3. Evidence of Heating-System Failure

Figure Above: Seized radiator bleed valve at point of catastrophic failure. The valve mechanism is visibly corroded and immobile, preventing isolation of the water supply and causing uncontrolled discharge. This constitutes a direct breach of landlord repair and safety duties. Legal paperwork is visible beneath the valve, demonstrating secondary consequential harm arising from the initial mechanical failure.

a. Radiator Valve Failure

Photographic evidence shows the radiator bleed/isolation valve located adjacent to a primary workspace. The valve exhibits visible corrosion, including verdigris deposits around the spindle and nut, indicating long-term deterioration and lack of maintenance.

During a routine bleed operation a normal domestic safety procedure the valve failed mechanically, ejecting water under pressure. Two to three buckets of water were discharged before containment could be improvised. No functional shut-off mechanism was available.

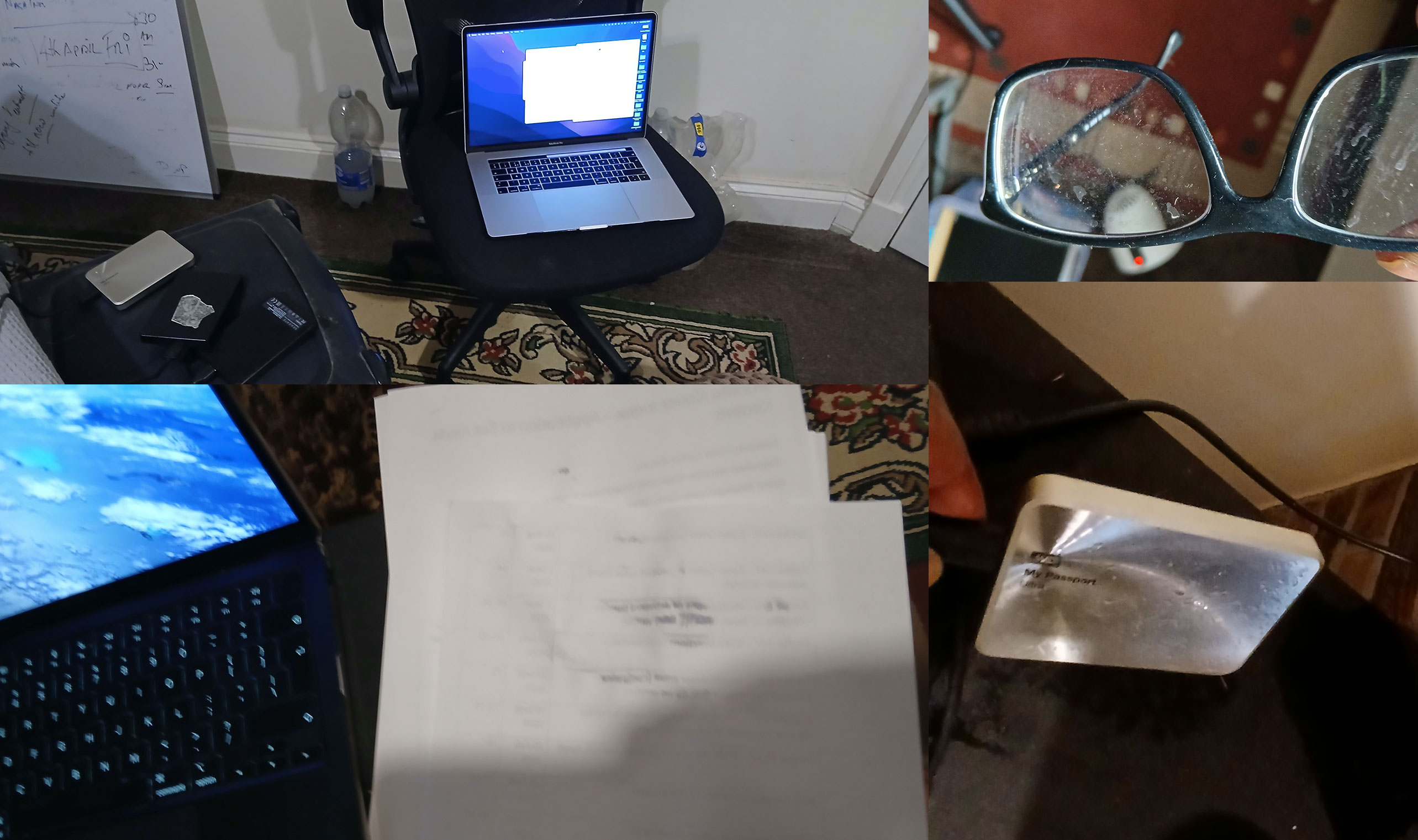

Figure Above: Composite images showing the immediate impact of the water discharge on the claimant’s working environment. Two laptops are visible, including a MacBook Pro directly exposed to water ingress. Legal papers and printed evidence were soaked, an external hard drive was splashed, and contaminated water residue is visible on the claimant’s glasses. The images document dirty water contact with electronic equipment and legal materials, evidencing both property damage and direct interference with active litigation documents.

b. Consequential Water Damage

Water entered the immediate workspace, contacting:

- live electrical sockets and cabling,

- legal bundles and loose evidential papers,

- computer peripherals, external storage devices, and a laptop,

- furniture and flooring.

Figure Above: Interior living and working space following a single incident of water ingress from the bathroom above. A bucket was placed temporarily to collect dripping water; contact between the bucket and the wall caused superficial scraping and disturbance of wallpaper that had become wet during the incident. The surrounding images show the proximity of the leak area to furniture, documents, and computer equipment within the primary living space, illustrating the immediate impact of the incident on habitability and use of the room.

The incident required emergency relocation of equipment and documents while water was actively flowing, under conditions of darkness following an electrical trip.

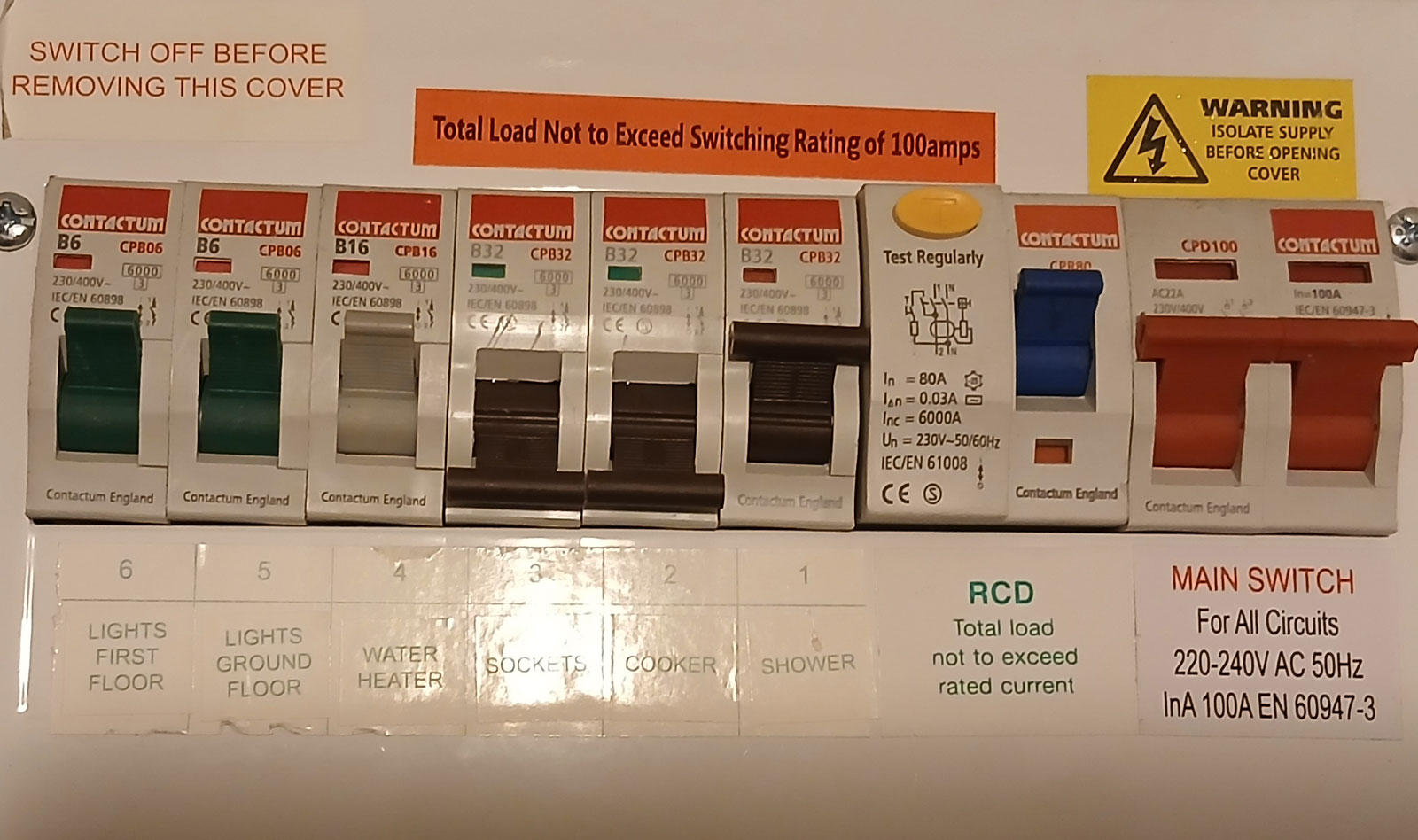

Figure Above: Domestic consumer unit showing legacy electrical configuration with multiple final circuits grouped without individual RCD protection. The sockets serving both ground and first floor are supplied via a single breaker, with shower and cooker circuits routed adjacent, demonstrating outdated circuit segregation and elevated fire and shock risk where water ingress and damp conditions were present elsewhere in the property.

4. Electrical Infrastructure as a Compounding Hazard

Separate photographic evidence documents the property’s electrical consumer unit. All socket outlets across the premises are connected to a single B32 breaker, with no separation between upstairs and downstairs circuits.

This configuration contravenes BS 7671:2018 Regulation 314.1, which requires installations to be divided into circuits to avoid danger and facilitate safe isolation. During the water-ingress incident, this design prevented selective isolation of affected areas, forcing total loss of power for several hours. On re-energisation, audible socket crackling occurred, confirming ongoing electrical danger.

The electrical defect materially exacerbated the risk posed by the plumbing failure, creating a combined electrocution and fire hazard.

Figure Above: Ceiling light and surrounding plaster damaged by prolonged water ingress originating from the bathroom above.

(1) Current condition showing residual staining and surface deformation following repeated moisture exposure.

(2) Prior condition showing active structural failure around the light fitting, including cracking, material loss, and mould growth caused by bathroom water leakage into the ceiling void adjacent to an electrical fitting.

(3) Condition following an improvised cosmetic repair using tape and paint, concealing the damage without repairing the bathroom leak source, addressing mould contamination, or mitigating the associated electrical safety risk.

5. Improvised Containment and Secondary Hazards

With no landlord or local-authority intervention, containment of the water discharge was left entirely to the occupant. A heavy bucket was forced between the desk and wall to intercept the continuing leak from the failed radiator valve. This action caused further tearing and deterioration of plaster already compromised by damp and previous disrepair.

Crucially, the water discharge and emergency containment occurred directly beneath a wall-mounted light fitting positioned above a live wall socket. The fitting forms part of the original electrical defects at the property and contains exposed, permanently live wiring, with no local isolation switch. Water was observed striking the wall surface in the immediate vicinity of both the socket and the light fitting.

Photographic evidence shows:

- standing water adjacent to the wall socket,

- the bucket positioned below the light fitting,

- exposed wiring within the light fitting above the impact zone, and

- soaked carpet beneath the occupant’s feet at the time of the incident.

Because the electrical installation lacks circuit separation, the affected area could not be selectively isolated. The result was a full loss of power when the breaker tripped, followed by audible crackling from a socket when power was later restored, necessitating prolonged shutdown.

The configuration created an immediate electrocution and fire risk: uncontrolled water, exposed live wiring in the wall-mounted light fitting, a live socket below, damaged plaster, and a wet floor surface, all within a confined working area. The occupant was forced to operate in this environment while medically vulnerable and without footwear.

These containment measures were neither safe nor sustainable. They demonstrate a complete absence of safeguarding, forcing improvised action under life-threatening conditions. The proximity of water to the wall-mounted light fitting with exposed live conductors constitutes a severe secondary hazard arising directly from the original mechanical failure and prolonged neglect.

6. Impact on Legal Infrastructure and Access to Justice

Legal documents and evidential materials were soaked or narrowly avoided destruction. Laptop central to legal drafting and evidence storage was spared only because water-soaked papers absorbed the initial discharge.

The workspace was forcibly reconfigured under unsafe conditions, beneath a ceiling bulge and defective light fitting. These circumstances interfered directly with the ability to prepare and conduct ongoing litigation, engaging the right to a fair trial and the peaceful enjoyment of possessions.

7. Local-Authority Non-Action

Under the Housing Act 2004 and the Housing Health and Safety Rating System, local authorities are required to inspect and act when notified of Category 1 hazards, including excess cold, scalding risk, electrical danger, damp, and structural instability.

Despite notification, no inspection was undertaken, no hazard recorded, and no enforcement action issued. Instead, unrelated administrative enforcement was pursued against the same individual. This constitutes institutional inversion: the reporter of danger was penalised while the hazard was ignored.

8. Judicial Suppression of Safety Evidence

In the related civil and possession proceedings (M04ZA309 and M00RG751), evidence of the electrical and plumbing hazards was submitted within N244 applications. Receipt was confirmed at the administrative level, yet the evidence was not logged by the receiving court. Orders were subsequently issued as if no safety issues existed.

This suppression removed critical life-safety material from judicial consideration and enabled possession pressure to continue without regard to risk.

9. Legal Basis

I. Landlord and Tenant Act 1985, s.11 — Installations for Heating, Water, Electricity

Section 11(1)(b)

“In a lease to which this section applies there is implied a covenant by the lessor—

… (b) to keep in repair and proper working order the installations in the dwelling-house for the supply of water, gas and electricity … and for space heating and heating water.”

Legal Duty

The landlord must keep installations for heating, water and electricity in repair and in proper working order throughout the tenancy, including associated valves, pipework, consumer unit safety, and safe functioning of supply systems.

Breach Identified

A corroded radiator bleed/isolation valve catastrophically failed during routine use, discharging uncontrolled water into an active workspace adjacent to live electrics. Electrical infrastructure was unsafe and incapable of safe isolation. These facts establish failure to keep the relevant installations in repair and proper working order.

II. Defective Premises Act 1972, s.4 — Foreseeable Harm from Defects

Section 4(1)

“Where premises are let under a tenancy, the landlord owes to all persons who might reasonably be expected to be affected by defects in the state of the premises a duty to take such care as is reasonable in all the circumstances to see that they are reasonably safe from personal injury or from damage to their property caused by a relevant defect.”

Legal Duty

The landlord must take reasonable care to ensure occupants and others are reasonably safe from personal injury and property damage arising from relevant defects in the premises and installations.

Breach Identified

Known/visible degradation (corrosion) and failure-prone installations were left unremedied. The resulting water discharge created foreseeable risks of electrocution, slips, and damage to equipment and documents. Reasonable care to prevent injury/property damage was not taken.

III. Homes (Fitness for Human Habitation) Act 2018 — Unfit Dwelling

Section 9A(1)

“In a lease to which this section applies, there is implied a covenant by the lessor that the dwelling is fit for human habitation at the time the lease is granted … and will remain fit for human habitation during the term of the lease.”

Legal Duty

The landlord must ensure the dwelling is and remains fit for human habitation, including safety from serious hazards arising from disrepair, water ingress, and electrical/fire risk.

Breach Identified

The dwelling was occupied with serious hazards: uncontrolled water release risk, unsafe electrics, and compounding conditions affecting habitability and safety. The property was not kept fit for habitation during the term.

IV. Electrical Safety Standards in the Private Rented Sector (England) Regulations 2020 — Electrical Safety Standards

Regulation 3(1)

“A private landlord who grants or intends to grant a specified tenancy must ensure that the electrical safety standards are met during any period when the residential premises are occupied under a specified tenancy.”

Legal Duty

The landlord must ensure electrical installations comply with applicable safety standards (including safe circuit design, testing, and remedial works) and remain safe throughout occupation.

Breach Identified

All socket outlets were effectively placed on a single circuit (single B32 breaker), preventing safe isolation during a water-ingress event and causing total power loss. Audible socket crackling on re-energisation indicates continuing danger. Electrical safety standards were not met.

V. Housing Act 2004 (HHSRS) — Category 1 Hazard Enforcement Failure

Housing Act 2004, Part 1 (HHSRS)

Where a local housing authority identifies a Category 1 hazard, it has a duty to take the appropriate enforcement action.

Legal Duty

Upon notification and/or identification of Category 1 hazards (including electrical shock, fire risk, damp/mould, excess cold, structural instability), the local authority must inspect, record, and take appropriate enforcement action.

Breach Identified

Despite notification of serious hazards, no effective inspection/enforcement is evidenced, and hazards were allowed to persist. Life-safety conditions remained unaddressed, constituting failure to discharge statutory safeguarding/enforcement duties.

VI. Equality Act 2010 (ss.20–21, s.149) — Reasonable Adjustments and Public Sector Equality Duty

Section 20(3)

“The first requirement is a requirement, where a provision, criterion or practice of A’s puts a disabled person at a substantial disadvantage … to take such steps as it is reasonable to have to take to avoid the disadvantage.”

Section 21(1)

“A failure to comply with the first, second or third requirement is a failure to comply with a duty to make reasonable adjustments.”

Section 149(1)

“A public authority must, in the exercise of its functions, have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination … [and] advance equality of opportunity …”

Legal Duty

Where disability/vulnerability is known, authorities must (a) take reasonable steps to avoid substantial disadvantage, and (b) exercise housing/enforcement functions with due regard to eliminating discrimination and advancing equality of opportunity.

Breach Identified

Known medical vulnerability was not accommodated in the response to unsafe housing conditions and enforcement actions. Failure to adjust safeguarding/enforcement approach, while hazards persisted, placed the individual at substantial disadvantage and breached both the adjustment duty and the PSED.

VII. Human Rights Act 1998 — Articles 2, 6, and 8 ECHR

Article 2

“Everyone’s right to life shall be protected by law.”

Article 6(1)

“In the determination of his civil rights and obligations … everyone is entitled to a fair … hearing …”

Article 8(1)

“Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.”

Legal Duty

Public bodies (and courts as state organs) must act compatibly with Convention rights: protect life where real and immediate risk arises, ensure fairness and effective access to justice, and avoid unlawful or disproportionate interference with the home/private life.

Breach Identified

Life-risk hazards (water + electrics + fire risk) were allowed to persist without effective safeguarding response. Evidence relevant to safety and proceedings was not properly logged/acted upon, impairing effective participation and preparation in litigation. Unsafe interference with the home and private life continued.

VIII. First Protocol, Article 1 ECHR — Peaceful Enjoyment of Possessions

A1P1

“Every natural or legal person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions …”

Legal Duty

State action/inaction must not unjustifiably or disproportionately interfere with possessions; where interference occurs, it must be lawful, necessary, and proportionate.

Breach Identified

Water discharge endangered and damaged legal papers and electronic devices integral to daily living and litigation. The continuing hazard environment and disruption to use/enjoyment of possessions constitutes interference not justified by any lawful, proportionate safeguarding response.

10. Truthfarian Equivalence (Internal Classification)

Truthfarian classifies the radiator valve catastrophe and the forced containment beside live electrics as a Safeguarding Collapse Event with secondary Evidence-Integrity Interference, where preventable risk is permitted to mature into life-threatening hazard through multi-agency non-action (landlord + local authority + court process). Under the Truthfarian equilibrium framework, this is recorded as state-produced hazard continuity: hazard persistence beyond notice, with no protective intervention, resulting in compounded harm across home safety, health stability, and access-to-justice continuity.

If you want the PHM line directly beneath it (optional, but consistent with your prior articles), use:

PHM Equivalence (Truthfarian Metric Line)

In PHM terms, this is an unmitigated hazard progression: systemic cost accumulation increases while protective action remains null, producing a non-equilibrating harm state.

$H_t = f(\Delta C_t - \Delta \Omega_t)$

11. Conclusion

The radiator-valve failure was not a maintenance dispute. It was the manifestation of a systemic safeguarding collapse involving:

- landlord neglect of basic safety obligations,

- local-authority failure to inspect or enforce,

- judicial failure to record and consider safety evidence,

- cumulative exposure to life-risk conditions,

- and unchecked harm escalation.

Taken together, the evidence demonstrates disrepair negligence, breach of statutory duty, safeguarding failure, and human-rights interference with foreseeable and preventable consequences. This disclosure is published in the public interest as empirical evidence of institutional failure within housing, regulatory, and judicial systems.