1. Overview — When a Defendant Communicates Outside Permitted Channels

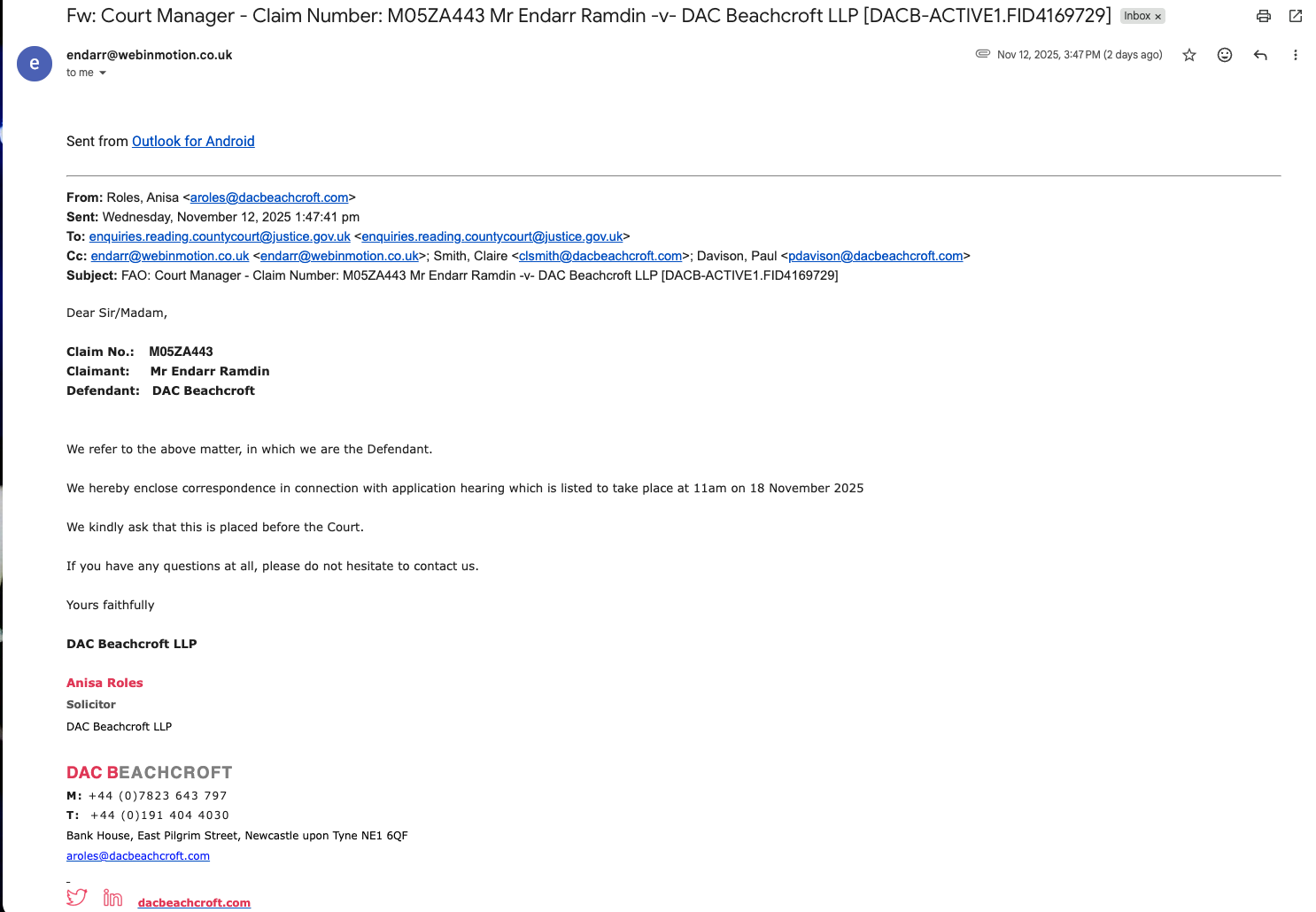

On 12 November 2025, DAC Beachcroft LLP issued an email to Reading County Court and simultaneously sent it directly to the Claimant’s private email address. The Claimant did not designate email as an address for service, nor did the Defendant seek permission to communicate through this channel.

Under the Civil Procedure Rules and Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) conduct standards, this form of contact is not authorised during active proceedings.

The communication is examined below using the forensic structure applied across Truthfarian disclosures.

2. Evidence – Extract of the 12 November 2025 Email

The email from Anisa Roles, solicitor at DAC Beachcroft LLP, included:

- correspondence intended to influence the upcoming application hearing,

- direction to “place this before the Court”,

- and direct email transmission to the Claimant,

- despite the absence of a Defence and absence of standing to advance disposal.

This disclosure examines the procedural implications of this act.

3. CPR Framework – Communication and Service

I. CPR r.6.23 — “Address for Service”

Service must occur at:

an address specified on the claim form; or

an address designated in writing by the party.

Analysis:

The Claimant never designated email as a service address.

Direct communication to the Claimant's private email therefore does not meet CPR requirements and constitutes a procedural irregularity.

II. CPR r.6.3 — “Methods of Service”

Permitted methods include:

personal service,

first-class post,

document exchange,

or service by email only if explicitly agreed.

Analysis:

No agreement exists.

DAC Beachcroft’s method is inconsistent with CPR 6.3.

III. CPR Part 1 — Overriding Objective

Courts and parties must conduct litigation:

fairly,

transparently,

consistently,

and without creating imbalance.

Analysis:

Contacting a litigant in person through an unagreed channel during a live claim undermines procedural neutrality.

4. SRA Code of Conduct – Communication with Litigants in Person

Solicitors must:

act with integrity (Principle 2),

uphold the proper administration of justice (Principle 1),

ensure communications with litigants in person are appropriate (Code 8.1),

avoid taking advantage of unfamiliarity (Code 1.4).

Analysis:

Direct email communication risks procedural pressure, especially where:

- no Defence has been filed,

- the Defendant lacks standing for disposal,

- the Claimant is unrepresented,

- and the application hearing concerns an amendment (N244) the Defendant cannot pre-empt.

The 12 November email does not meet SRA standards of solicitor–litigant neutrality.

5. Jurisdictional Analysis – Venue and Standing

I. No Standing Without Defence (CPR r.16.5)

A Defendant cannot seek:

strike-out under CPR 3.4, or

summary judgment under CPR 24,

without filing a Defence.

Analysis:

No Defence exists.

DAC Beachcroft’s correspondence therefore cannot advance disposal or influence venue.

II. Practice Direction 7A, Paragraphs 2.4 to 2.6 — High-Value and Complex Claims Requiring High Court Jurisdiction

Practice Direction 7A, Paragraph 2.4 provides that claims which exceed the financial limits of the County Court, or which raise issues of complexity or public importance, must be issued in the High Court unless otherwise directed.

Practice Direction 7A, Paragraph 2.5 further states that where a claim includes allegations relating to public authorities, significant points of law, or matters of substantial value, the appropriate forum is the High Court, specifically the King’s Bench Division.

Practice Direction 7A, Paragraph 2.6 confirms that claims involving complex civil-rights arguments, data-governance harms, public-sector decision-making, or multi-party institutional involvement fall within the category of cases that must be transferred to the High Court even if initially issued in the County Court Business Centre.

Application to This Case

The Claimant’s matters include:

- breaches of statutory duty by public bodies,

- data-governance failures crossing multiple legal regimes,

- institutional irregularities affecting access to justice,

- disability-rights and equality-rights arguments,

- and a financial valuation exceeding £10,000,000 as set out in the amended Particulars of Claim.

These characteristics place the matter squarely within the High Court’s specialist jurisdiction under Practice Direction 7A, Paragraphs 2.4 to 2.6, and are incompatible with County Court allocation.

Analysis

Despite the mandatory criteria under Practice Direction 7A, the Defendant’s solicitors issued correspondence encouraging the continued handling of the claim by the County Court and seeking to influence the listing of an application hearing at that level.

This position is misaligned with the jurisdictional requirements established by:

- Practice Direction 7A, Paragraph 2.4 (High-Value Claims)

- Practice Direction 7A, Paragraph 2.5 (Complexity and Public Authority Involvement)

- Practice Direction 7A, Paragraph 2.6 (Mandatory Transfer Criteria)

- Civil Procedure Rules, Part 30, Rule 30.3(2)(f)

(requiring transfer where the claim is of exceptional importance, value, or complexity)

The continued suggestion that County Court jurisdiction is appropriate conflicts with the procedural framework and disregards the mandatory transfer principles that govern claims of this character.

6. International Law – Rights Affected by Procedural Interference

I. ICCPR — International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

Article 2(3) — Right to effective remedy.

Article 14(1) — Equality before a competent, impartial tribunal.

Analysis:

Unauthorised communication affects equality of arms.

II. UDHR — Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Article 7 — Equality before the law.

Article 8 — Effective remedy.

Article 10 — Fair hearing.

Analysis:

Irregular solicitor–litigant contact during proceedings undermines fairness safeguards.

III. ECHR — European Convention on Human Rights (via HRA 1998)

Article 6 — Fair trial.

Article 8 — Data/privacy.

Article 13 — Effective remedy.

Analysis:

Direct email contact impacts transparency and procedural predictability, especially where venue and standing are contested.

7. Truthfarian Equilibrium Analysis

Let:

- 𝓟 = procedural integrity

- 𝓡 = rights recognition

- 𝓛 = lawfulness

- 𝓔 = ethical neutrality

Truthfarian equilibrium requires:

Eq(S)= f(P,R,L,E)

In this event:

- 𝓟 ↓ (unauthorised service)

- 𝓡 ↓ (litigant rights impacted)

- 𝓛 ↓ (CPR & SRA obligations not met)

- 𝓔 ↓ (professional neutrality reduced)

Thus:

Eq(S) →0

This evidences systemic procedural imbalance.

8. Conclusion — Procedural Deviation and Rights Impact

The 12 November 2025 email constitutes:

- unauthorised method of communication under CPR 6,

- inconsistent solicitor conduct under SRA Code,

- lack of standing under CPR 16.5,

- impact upon fair-trial rights (ECHR, ICCPR, UDHR),

- interference with proper jurisdictional pathway,

- and a pattern consistent with earlier Truthfarian disclosures of procedural irregularity.

This disclosure is filed under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 as verified evidence of procedural deviation during active civil proceedings.

9. Exhibits and Source Index

- Exhibit A — Email of 12 Nov 2025

Structural Impact Formula

The Structural Impact Score is defined as:

$SIS = \left( \sum_{i} w_i \cdot x_i \right)\!\left( 1 + \lambda \sum_{i\lt j} x_i x_j \right)$

Where:

$x_i$ are binary structural variables representing the presence (1) or absence (0) of each structural pattern, including:

- $P$ = Procedural Breakdown

- $C$ = Court / Authority Administrative Capture

- $D$ = Defence / Counterparty Interference

- $V$ = Vulnerability Amplifier

- $R$ = Rights / Regulatory Misstatement

- $I$ = Institutional Interlock

$w_i$ are the base weights assigned to each variable in the TruthFarian structural pattern model.

$\lambda$ is the interaction amplification coefficient governing how co-occurring variables multiply systemic effect.

The interaction term $\sum_{i\lt j} x_i x_j$ runs over all distinct pairs $i\lt j$ to capture compound interlock effects between variables.

Structural Impact Result

$SIS = (w_P + w_C + w_D + w_V + w_R + w_I)\cdot(1 + \lambda \cdot 15)$

Activated Structural Variables:

- $P = 1$

- $C = 1$

- $D = 1$

- $V = 1$

- $R = 1$

- $I = 1$

Interaction Pair Count: $15$ co-occurring variable pairs

Structural Impact Meaning

An $SIS$ at this level reflects systemic procedural interference by a regulated legal counterparty, rather than adversarial correspondence within normal litigation bounds.

The active configuration — procedural breakdown ($P$), administrative capture ($C$), counterparty interference ($D$), vulnerability amplification ($V$), rights and regulatory misstatement ($R$), and institutional interlock ($I$) — evidences coordinated pressure operating outside lawful procedural footing.

Co-occurring structural patterns amplify one another, confirming escalation beyond isolated correspondence into governance-level distortion. Within the TruthFarian Structural Pattern Model, this profile engages public-law thresholds concerning fairness, equality of arms, professional regulation, and institutional accountability.